Why a Search of Public Projects Should Be On Every Closing Checklist

From title reports to tax assessments and surveys, due diligence checklists provide a comprehensive way to ensure that all the complex and various demands and risks of a commercial real estate transaction are discovered and addressed on the front end to ensure no issues arise on the back end. Most transactions, however, typically overlook one important contingency – public projects. Valuable commercial real estate in a busy market can attract the need for roads and infrastructure. The government’s exercise of eminent domain for a public infrastructure project can affect any commercial or residential property in a project corridor at any time, but it rarely comes to mind in real estate transactions. The failure to investigate current pending or even future potential public projects that may impact the transaction or use of the property being sold could leave buyers and sellers with their money and investments at risk. This article offers a brief examination of eminent domain laws and shows why a public project review is a necessary element of due diligence in order to protect the transaction.

Eminent Domain Laws and Public Projects

By constitutional and statutory authority across all fifty states, every type of property and every property right are subject to being taken or damaged by a governmental entity in order to support a public project, provided that owners first receive “just compensation.”1 Just compensation includes the value of the real estate, improvements, fixtures, relocation costs, and sometimes business damages. In a handful of states, property owners are entitled to pursue a separate claim for business value or damages as part of just compensation for a taking of property.2

In a continuing effort to stay ahead of traffic and population growth, federal and state departments of transportation rely heavily on this authority and are busier than ever with infrastructure maintenance and expansion projects across the United States.3

The Georgia Department of Transportation for example is wrapping up one of its most active years,4 with more infrastructure projects on the horizon well into 2040.5

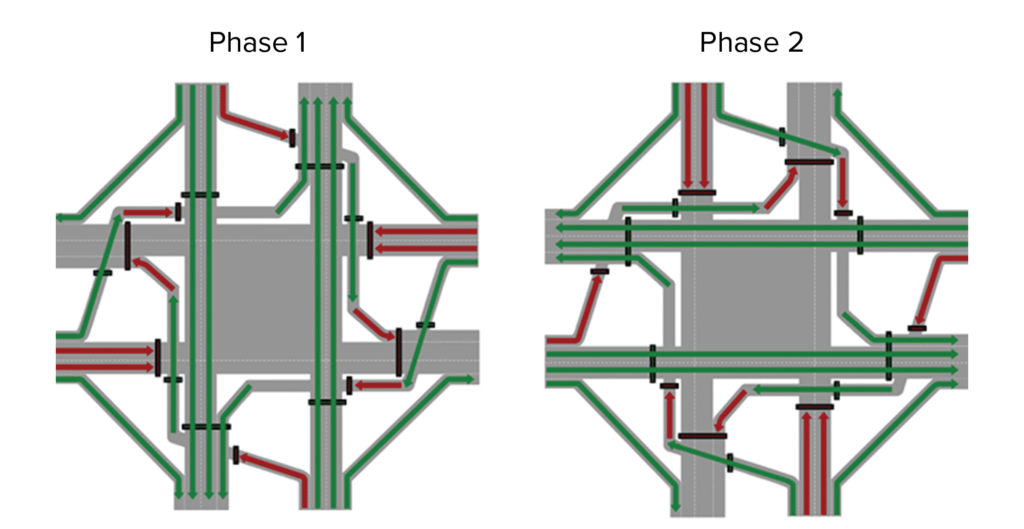

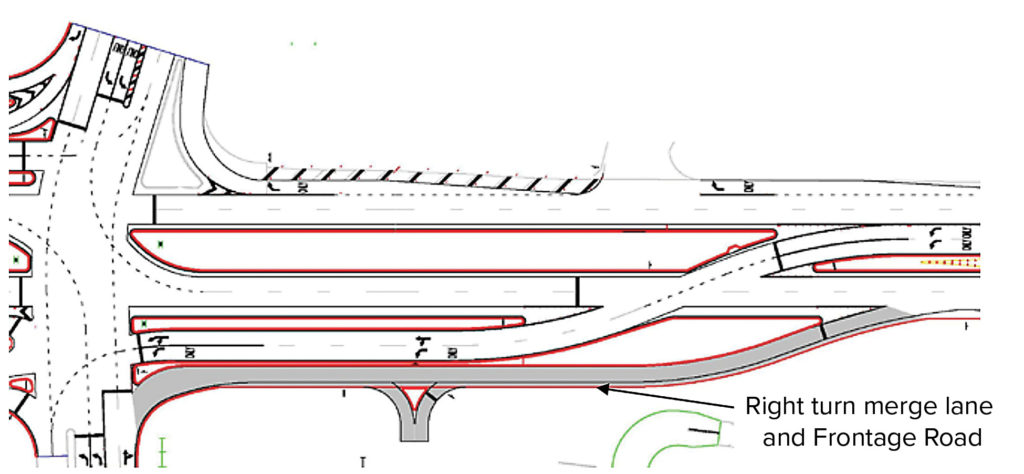

Likewise, municipal and county governments are becoming more adept at and willing to use eminent domain to address urbanization and demand for a localized tax base.6 These projects can be a barometer of current and projected economic growth, ensuring roads and utilities can accommodate increased traffic demands. However, it can come at a cost to individual properties and businesses. Transportation and public works entities are finding new and creative ways to balance these demands including the latest trend, the continuous flow intersection (“CFI”) or displaced left turn intersection.7 Intended to keep high volume traffic at highway intersections moving at a fast clip, the CFI design reduces left turns by preventing cross traffic (see Figure 1 and Figure 2, and Figure 3).8

Figure 1: Continuous Flow Intersection

(Crossover Displaced Left Turn)

Image courtesy of Parker Poe

Figure 2: GDOT Continuous Flow Project in Dawsonville, GA

Image courtesy of Parker Poe

In theory, the design works for avoiding traffic stacking and backups. In reality, it can be a killer for pin corner retail and commercial properties by preventing customers from convenient ingress and egress to the properties aligning the CFI.

Because it involves the taking or damaging of private ownership and use of property, the exercise of eminent domain can have serious financial, legal and physical consequences for a project. Minimizing the impacts caused by a public project and taking and/or maximizing compensation for owners requires navigating the authority that allows the taking of private property for public use. While eminent domain laws provide some protections for landowners that vary state by state,9 condemnation procedures generally include only the current owner of record, often ignoring potential or future buyers and the reality of the real estate market in which ownership, uses, and development change as growth continues. If the buyer fails to check for upcoming public projects, there is no safety net for the “buyer beware” rule and what a buyer doesn’t know at the time of the transaction can hurt. For sellers, a pending project may last ten years in the design phase, creating a cloud on title until the condemning authority pulls the trigger on the project. A taking is not a taking until a closing occurs, a declaration of taking is filed or a final ruling is issued and title shifts to the condemning authority.10

Figure 3: Displaced left turn intersection plan illustration in Baton Rouge, LA 11

Image courtesy of Parker Poe

There are no limits on when a condemning authority can seek to condemn regardless of a private transaction in progress, leaving buyers and sellers scrambling to claim rights to the land and the compensation.

Due Diligence and the Need for Public Project Review

Dealing with a public project may be rare for some. So what’s the real risk here? Whether a current or future project, or whether involving a direct taking of the property or merely a change in the market area, a project can result in a loss of some or all of the elements that attract the buyer to the property in the first place. With a retail property for example, a road widening can disturb front parking areas, severely damage access by changing them from full turns to right in/right out turns or include new retaining walls making the property unsightly or difficult to find.

So how best to reduce the risk of the unknown with a public project? Vetting pending or potential projects in and around the immediate market area as part of the initial due diligence process. If one is discovered, conduct a thorough and knowledgeable review of the project, including: (1) determining whether the project will directly affect the property with a taking, or directly affect the property by changing access, traffic flow or the market area; (2) analyzing the project plans and details to determine how the property will be reduced, impacted, and/or damaged by the project; (3) evaluating if these impacts on the property will not interfere with the future use of the property and thus, the sale transaction; and (4) confirming that the transaction can move forward as intended.

Failure to uncover or disclose a project can harm the parties to a transaction in a variety of ways. As part of a formal condemnation proceeding, a claim or right to compensation is typically assignable from seller to buyer. However, the taking, any resulting damage, and the condition of the remaining property must be fully understood and carefully described in the closing documents in order to protect these rights. An assignment of these rights can create conflicts as to who receives what and when. The seller may know what’s coming and receive all the compensation, leaving the buyer with no way to recover for a loss.

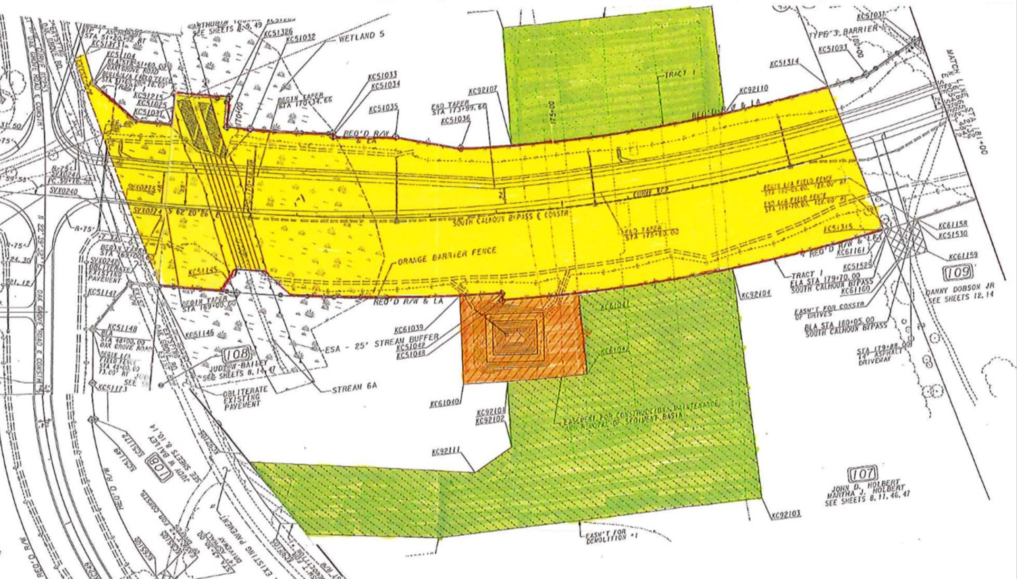

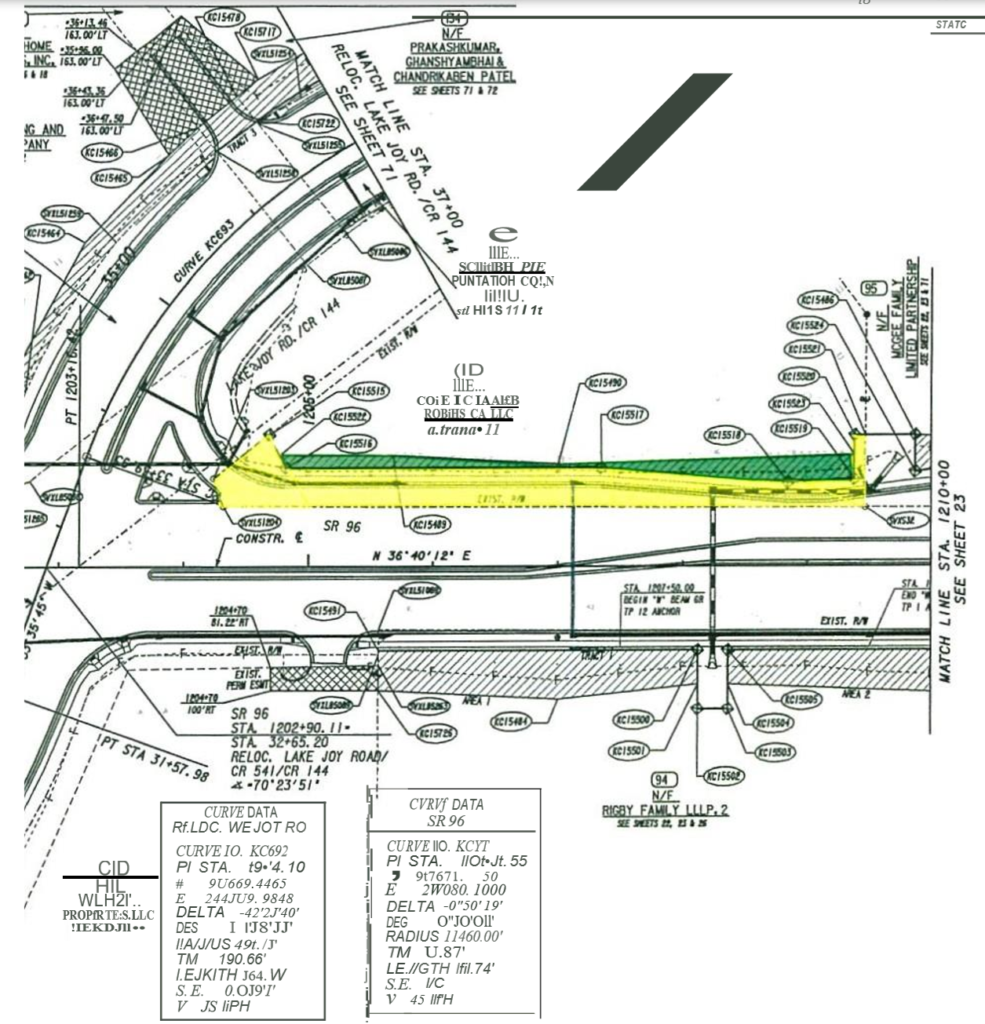

Furthermore, a review by someone unfamiliar with engineering or right of way project plans may miss major issues hidden in the hatch marks and cross sections such as a loss of existing access, elevation changes and uneconomic remnants. Understanding the reality of a complicated road project, such as the CFI discussed above, can be difficult without a trained eye and a qualified engineer to interpret the change of traffic flow and access and explain it in layman’s terms to the buyer or seller (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: GDOT Right of Way Plan

Showing a new bypass across agricultural land with no driveway to the property, and a total loss of existing access due to a shift in the existing road away from the property.

Image courtesy of Parker Poe

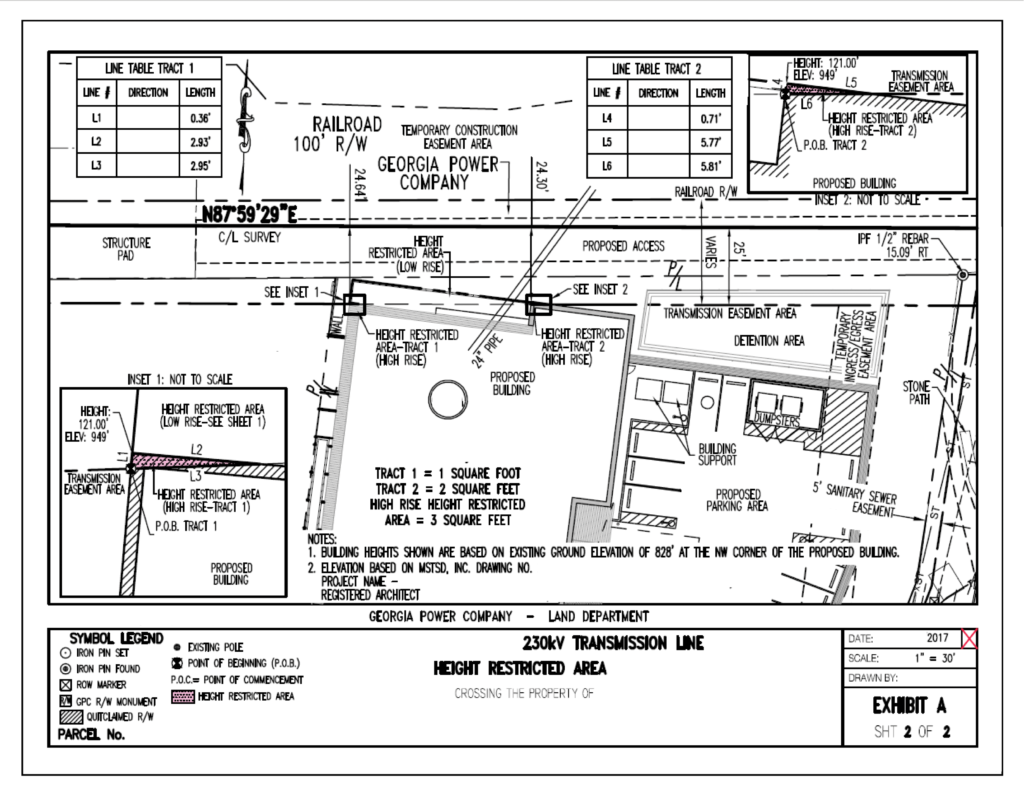

Likewise, a small area for a taking of fee or easement rights may look innocuous to an untrained eye, but condemnations often take more rights than the actual square footage of land. Damages can result from driveway closures and reduced access, retaining walls of undetermined heights, to utility relocations. The condemning authority may limit an owner’s use of their own land through vague language in the easements.

The remainder property may be damaged more or a second time by existing zoning requirements due to setbacks or buffers, parking and signage limitations (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Georgia Power Transmission Expansion Plan

Showing existing building and planned development encroaching into new easement with impacts caused by zoning building height limitations.

Image courtesy of Parker Poe

A thorough review can ensure a full understanding of any options to reduce these damages and how to pursue potential claims for recovery of just compensation.

A Practical Application of Public Project Review

As demonstrated in the example below, a lack of knowledge of how to evaluate plans and of the property itself can threaten not only the transaction, but the viability of the highest and best use of a national pharmacy retail location.

What was a right in/right out at the drive thru shown above turned into a fully closed driveway and loss of all access on the right of way plan in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Pre taking aerial of retail pharmacy store location in Warner Robins, GA

Image courtesy of Parker Poe

The driveway closure was not overtly stated or described in the plans, but upon closer inspection was shown as a former driveway in a lighter print. This important detail was missed during the vetting process in a transaction (see Figure 7). If a sale had closed, the property would have been in a remainder damaged condition without access and no recourse for the buyer. The property also had an existing lease, which the tenant could have terminated due to a loss of parking from the taking and loss of access. Ultimately, a right in driveway was clawed back during negotiations with the condemning authority.

Figure 7: GDOT Right of Way Plan

With driveway curbed over and drainage installation in its place

Image courtesy of Parker Poe

Knowing a public project is coming allows informed decisions, full and fair negotiations (both between the parties to a transaction and with the condemning entity) and proactive exploration of remedies. While construction of the public project may take years to complete, condemning authorities have a right to take the necessary property and property rights to support a project at any time, regardless of a pending closing. Once the eminent domain process has begun, it is very difficult to stop a public project entirely. Instead, owners can and should focus on negotiating compensation, and on reducing or mitigating the effects of a taking, in order to protect the property and its use including as part of a sale. •

Endnotes

1. See American Bar Association, Condemnation, Zoning & Land Use Committee, Fifty-State Survey: The Law of Eminent Domain, (William G. Blake ed., 2012). ↩

2. See id. ↩

3. See, e.g., Georgia Department of Transportation Planning Division, 2018 Statewide Strategic Transportation Plan, (2018), http://www.dot.ga.gov/InvestSmart/Documents/SSTP/Plan/2018SSTP-Final.pdf ↩

4. See Jim Parsons, Georgia DOT Steps Up to Meet Infrastructure Challenge, Engineering News Report Southeast, Feb. 26, 2018 (https://www.enr.com/articles/44046-georgia-dot-steps-up-to-meet-infrastructure-challenge). ↩

5. Id. ↩

6. See Chris Joyner, Watchdog: Georgia bill lets cities take blighted land for developers, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, March 29, 2017 (https://politics.myajc.com/news/state–regional-govt–politics/watchdog-georgia-bill-lets-cities-take-blighted-land-for-developers/CYHlIymNbqUH72G1GVT6zI/). See also Brentin Mock, The Deal That Might Just Break Georgia Into Pieces, Citylab, May 17, 2018 (https://www.citylab.com/equity/2018/05/the-deal-that-may-have-just-broken-georgia/560528/). ↩

7. See Federal Highway Administration, Alternative Intersections/Interchanges: Informational Report, (https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/research/safety/09060/09060). ↩

8. See Deb Weaver, Continuous Flow Intersections Are A Safe Bet for Motorists, November 30, 2017, (https://meadhunt.com/continuous-flow-intersections). ↩

9. See e.g., City of Marietta v. Summerour, 302 Ga. 645, 807 S.E.2d 324 (2017). See also American Bar Association, Condemnation, Zoning & Land Use Committee, supra note 1. ↩

10. See American Bar Association, Condemnation, Zoning & Land Use Committee, supra note 1 at 115-116. ↩

GDOT I-85 Bridge Project, Atlanta, GA. Photo courtesy of GDOT.

GDOT I-85 Bridge Project, Atlanta, GA. Photo courtesy of GDOT.