Recommendations by the CRE® Consulting Corps

The Counselors of Real Estate’s Consulting Corps delivered strategic guidance and an action plan to Naval Air Station Oceana. The third in this 4-part series explores public-private partnership options, presents examples of enhanced use leases and City-Base transaction, and describes the City-Base transaction critical path.

Read: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 4

Watch: Legal & Regulatory Issues

Reid Wilson, CRE, discusses legal & regulatory issues on March 31, 2021.

Options for Public-Private Partnership: What Public-Private Partnership Options are Available to Oceana?

The term “Public-Private Partnership” (also “P3” or “PPP”) is used to describe a broad variety of legal relationships between private parties and public entities relating to the use and development of land, usually long term (minimum 20 years). It may also be used to describe relationships between 2 or more public entities. Long-term leasing of government land for private development (often with related restrictions on use and government incentives supporting the development) is one common type of PPP. Of course, there are much more complex structures, but the lease vehicle is in frequent PPP use.

In the context of publicly owned land, the use of a PPP is usually considered to attract specialized real estate knowledge from the private sector to facilitate highest and best use of the land. Often, public entities consider their land assets as burdens rather than assets, plus lack “bench strength” in real estate development education and experience. In particular, real estate is not a core function nor competency. With financial challenges at all levels of government, different public entities are looking to PPPs to lighten their financial loads, particularly when the entity has non-essential real estate assets.

The public entity engaging in a PPP must first confirm its authority. In the public sector, there are often limits on the “delegation of authority” from the public entity to a private citizen/entity. The Navy is limited in its current authority to transact, so its first step is to evaluate its options.

First Steps

As with any transaction, the first step in the process is for Naval Air Station (NAS) Oceana be certain of its objectives and options before moving forward. As we will explore further, a cost baseline analysis is critical to understanding how the Navy’s costs align with private sector costs. However, the most important step is to establish a Taskforce comprised of representatives of the City of Virginia Beach and the Navy. This “Oceana Future Base Design Taskforce” should have specific attributes.

Oceana Future Base Design Taskforce Attributes

- The members should be limited in number; the fewer the better.

- Members should have a clear understanding of FBD, the 2005 BRAC experience, City-Base Transactions, and this report.

- Members should be “authorized” to represent their parties’ interests.

- Members should be prepared to support interests of both parties.

- Members must be prepared to communicate progress and milestones with their constituents jointly.

- Members should be supported by a facilitator experienced with this process.

The first action for the Taskforce is to establish fundamental objectives through a non-binding letter of intent and to secure a facilitator whose sole responsibility is to help both parties achieve their objectives. The next step, and first duty of the Taskforce, is to jointly develop an options matrix to examine all options and determine which course of action will offer the Navy and City the best opportunity to achieve their desired results. While Oceana’s options may be endless, the CRE® Consulting Corps team recommends the Taskforce select no more than five (5), and one option should always be Status Quo. Options might include:

- Status Quo (no changes of any kind)

- Cantonment (keep what you wish and dispose of the rest)

- Enhanced Use Lease (EUL) (Navy negotiates directly with multiple private sector tenants)

- EUL to City (Navy executes a single lease to City who subleases to multiple tenants)

- Transfer & Leaseback (Navy transfers title & leases back from City)

Figure 1: Sample Options Matrix*

| Considerations | Option 1 | Option 2 | Option 3 | Option 4 | Option 5 |

| Who owns the assets (real property)? | Navy | Navy | Navy | Navy | City |

| Who pays Base Operations Support (BOS)? | Navy | Navy or Future Owner | Navy & Developer Share Costs | Navy & City Share Costs | City & Navy Pays Some Costs |

| Does City provide municipal services? | Not at this Time | Not in Cantonment Areas | Some Possibly | Yes | Yes |

| Who controls disposal of utilities? | Navy | Navy & GSA | Navy | Navy | Navy or City |

| Who determines use of property? | Navy | Navy & GSA | Navy | City w/ Navy Approval | City w/ Navy Approval |

| Do we need partners? | No | No/Maybe | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| How complex would this be? | Easy | Complex | Complex | Complex | Complex |

| Other Considerations | TBD | TBD | TBD | TBD | TBD |

*This sample Options Matrix is notional, and some responses to these considerations may differ in this instance.

Additional considerations might include:

- What is the basis for authority?

- Jurisdictional Status?

- Who determines the zoned land use?

- What legal authorities control the implementation of the option?

- What is the lease cost?

- Can the property be taxed?

- What are the business case analysis criteria?

- How will revenues accrue to the Navy?

- Who will fund infrastructure expansion to accommodate development?

- Who pays Base Ops?

- What is the return on investment made by the Navy to facilitate development?

- While additional options and considerations may also apply, developing an options matrix is one of the first tasks in the process.

While additional options and considerations may also apply, developing an options matrix should be the first task in the process.

Status Quo Analysis

Status Quo suggests NAS Oceana does nothing and hopes the Navy funds its BOS requirement fully, forever, and provides additional funding to bring its facilities up to its current standards. Under different circumstances, it might be acceptable to assume this scenario is possible, though not probable. However, trading BOS funds for longer deployments or additional capabilities is a pattern that is not unique to the Navy. It seems unlikely NAS Oceana will ever be funded at its full BOS requirement or provided the additional funding required to bring existing facilities back to their original condition, let alone a modern equivalent.

The private sector contrasts with the Navy’s model funding deferred maintenance issues only when they become chronic. Rather, in the private sector, every property owner works to ensure their product meets the needs of the tenant in order to achieve their investment objectives. Based on the Navy’s pattern of funding BOS at NAS Oceana it seems clear the status quo is not an option for consideration.

Shared Services Agreement Analysis

A Shared Services Agreement allows the Navy to “purchase” services from a local government entity. This authority is commonly used to relieve the installation of BOS activities and reduce their associated costs. The Shared Services Agreement is technically called an “Intergovernmental Support Agreement” and is authorized by 10 USC 2679. The Navy may contract with a local government to provide services being provided by that local government to others, for up to 10 years. Normal procurement procedures are avoided. The local government need pay only the normal wages, not Davis-Bacon wages. The local government may provide the services using its own employees or may contract for the services. The terms of the agreement are such as approved by the Secretary of the Navy. This PPP has been reviewed by the General Accounting Office (GAO).1 Per the GAO report, as of 2018, there were 4 similar PPPs involving Navy installations and 4 more for Marine installations.

The number and type of services is left up to each installation but could include the following:

- Emergency Medical

- Street Maintenance

- Traffic & Signal Markings

- Streetlights

- Parks & Recreation (grounds Maintenance)

- Animal Control

- Code Compliance

- Building Inspections

- Planning

- Police

- Fire

- Other

These services and more are routinely provided by Cities to their residents and businesses. The Navy benefits through reduced labor and materials costs by tapping into the City’s much larger and more efficient resources. The City also benefits, by expanding its service areas and increasing its own economies of scale. This additional efficiency results in better pricing for the Navy and local taxpayers alike. NAS Oceana may enter into a Shared Services Agreement with any City, but realistically, the logical candidate is the City of Virginia Beach, which indicated its interest in investigating any appropriate PPP with the Navy in support of Oceana.

We note that the same services which may be provided via a shared services agreement, may also be provided as in-kind services as part of the compensation for an EUL (discussed below).

Critical Elements for Success

Like any business agreement, there must be mutual benefit. The City of Virginia Beach has adopted as part of its governmental goals to support the success of Oceana. As stated in the City of Virginia Beach Comprehensive Plan Sec. 1.6, “The City supports a continued strong military presence, both now and in the years to come.” The Navy must reduce its base ops budget. The mutual benefit is clear.

- Defining the Service

- The Navy must clearly define the type of service, the standards and the timeliness/frequency.

- The City must determine it has the capability to deliver the service.

- The standards must be clearly stated.

- A quality assurance process should be included.

- An appropriate problem resolution process should be agreed upon to reduce disputes.

- Financial Value

- The Navy must correctly calculate its true cost for the services to be out-sourced- direct and indirect, capital and maintenance, personnel and management (and education/training), time commitment (Cost Baseline Analysis).

- The City must also outline its costs for the Navy.

- The City should receive full compensation for its expenses.

- There must be sufficient delta for the Navy to out-source the service.

- Contract Period

- Max. 10 years, but an appropriate initial term would be 2-5 years. One year would be too short, as time should be given for appropriate transition.

- The Navy should retain a termination for cause or necessity without cost and a termination for convenience with a reasonable fee.

- Lessons Learned

- The Navy should communicate with Navy/ Marine installations with current Shared Services Agreements for lessons learned and best practices.

- The Navy should follow the recommendations in the GAO report.

The benefits of a Shared Services Agreement are two-fold: the Navy receives municipal services from a larger and more efficient organization, and the City is able to support a primary employer and increase its own operational efficiency. Both attributes must be present for the benefits of this agreement to achieve maximum potential for the Navy. This agreement is not the only option available, and elements can be used as in-kind consideration in combination with an EUL or City-Base transaction. It can be executed preemptively and then be incorporated into other agreements later. Overall, it is a flexible tool for the Navy to reduce BOS costs.

Enhanced Use Lease Analysis

An EUL is a lease of land, or land and buildings, that are excess to the needs of the government but not surplus prompting federal screening or a sale of the property. The EUL, or Enhanced Use Lease, is authorized by 10 USC 2667. If this option is selected, it would not preclude other transaction options described in this report.

The Navy uses the term Out Lease, but due to general use of the term EUL by other Armed Services, this report uses the term EUL. Use of EULs by the Armed Forces has been reviewed by the GAO. While relatively few EULs have been used by the Navy, the Air Force promulgated an Enhanced Use Lease Playbook, with a detailed process chart and example EUL form.2

Like any lease, there is a wide variety of possible business provisions. The following are some material provisions:

Terms:

- 5 years, but longer if the Sec. of the Navy determines it is in the public interest. (Note: a 5-year term is not capable of supporting a functional PPP, so all EULs will have lease terms of at least 20-30 years, generally with renewal terms of 5-10 years). Other services have settled on 50-year base term with a single 25-year renewal term for a total possible period of 75 years as the longest lease term.

- A 1st right to buy the land may be granted (effective if the lease is revoked by the Navy to permit sale under other legal authority).

- Rent may be:

- Cash, which must be deposited in a special account with the Treasury.

- Min. 50% likely available to Oceana for facilities.

- Remainder is available to the Sec. of Navy for other bases.

- In-kind services to Oceana (See, Sec. III(b) below).

- If for Morale, Welfare, and Recreation (MWR) services, restrictions may prohibit competition with MWR facilities or require such services (or compensation) if MWR facilities are eliminated, and if waived, notice to Congressional Defense Committees of the waiver and the reason is required.

- Must state “…if and to the extent that the leased property is later made taxable by State or local governments under an Act of the Congress, the lease shall be renegotiated.” See 10 USC 2667 (f)

- Cash, which must be deposited in a special account with the Treasury.

- Leaseback by the Navy is permitted, limited to $500,000 annual rent.

- In-kind services (see following discussion).

In-kind Compensation for EULs

The law requires that fair market value or rent must be paid for use of government land. For a Navy EUL, that rent may be paid in money or “in-kind services.” In-kind services are services provided to the Navy (usually the installation where the land is leased).

Examples:

- Services listed under a Shared Services Agreement (above)

- Repair or restoration of improvements

- Construction of new improvements

- Maintenance of improvements

- Providing facilities with services (such as MWR)

- Utilities

- Planning

- Other services relating to Navy activities approved by the Sec. of the Navy

NAS Oceana may be able to collect in-kind services by having the tenant pay all or a portion of specific external costs or vendor bills.

In-kind services may be performed at Oceana or other Navy facilities. If rent is paid in cash, then half must be paid to headquarters for the benefit of the Navy, and the Navy may (but is not required to) split 50% with the local installation to be used for facilities and maintenance. The use of in-kind services permits Oceana to retain 100% of the benefit of the EUL. In-kind services may also include relief from certain expenditures (utility bills, grounds maintenance, contract services, etc.). NAS Oceana may be able to collect in-kind services by having the tenant pay all or a portion of specific external costs or vendor bills.

Possible EUL Partners

Possible EUL partners could come from either the public or private sector. The type of partner depends on the type of EUL:

Site-Specific EUL

The partner is almost certainly a user of the land, such as a public utility, a manufacturer, an industrial company, and the like. A possible partner could include a commercial landlord, like a developer/operator of a business or industrial park, which would build structures intended for lease (in this case, sublease). Nationally recognized developers include Hines, Trammel Crow, Duke, and ProLogis. Certainly, there are local qualified developers. An appropriate partner for a site-specific EUL must have the economic capacity to perform the requirements specified in the lease (paying rent/providing in-kind services/ complying with contractual covenants).

Master EUL (with Sub-Tenants)

If the Navy were to lease all or a substantial portion of its underutilized land in a “master” EUL, with the expectation that the tenant would sublease portions to other parties for use or development, they should seek a different type of partner for a PPP. In the private sector, those partners could be large-scale, experienced and well-funded developers able to commit to a long-term relationship. There are many such developers in major real estate markets, but it is unlikely the Navy will find this type of developer in the Hampton Roads area. In the public sector, an Economic Development Authority (EDA) is a logical option.

EDAs are experienced and focused on bringing new business to the area and promoting retention and expansion of existing businesses. Site selection is a major issue for business, and EDAs understand the local real estate market, what sites are available (and “shovel ready” for development), and the local real estate players who can support businesses. Furthermore, the Virginia Beach EDA has the ability to provide public financing for infrastructure and development projects.

Successful EUL Examples

Grand Forks AFB (Drone Research Park) – Master EUL

In 2015, the Air Force leased 217 acres to a private development entity for 50 years with a 25-year renewal. The developer then sources private sector users focused on drone development, and subleases smaller sites to users. The developer brings expertise in industrial development. The military need not deal with the end-user (and vice versa). Certain limitations and protections for the military are incorporated into the EUL and the subleases. This lease is well negotiated on both sides and is an excellent example for a Master EUL.

San Diego Naval Station EUL

A 2020 Navy EUL is a 30 year base term (plus 36-year renewal option) lease at San Diego, California to Marine Group Boat Works, a local marine services firm (Contract No. S-20-RP-00108 Naval Base San Diego N00245).

More detailed information about EULs, their use by the Navy, their review at GAO, their varied uses and a detailed process analysis and form are in the Enhanced Use Lease Playbook.3

Proposed Master EUL for NAS Oceana

Oceana’s real estate assets are varied in their adaptability and desirability for private sector development and hinge upon a number of conditions:

- Environmental conditions and cost to remediate/mitigate

- Wetlands

- Archeological

- Contamination

- Location

- Distance to I-264 and the Port

- Adjacent road system and capacity

- Adjacent uses

- Site Readiness

- Former Ag. Land

- Natural woodlands

- Accident Protection Zone (APZ)/Noise zones and related use limitations

- Shape and size

Prior to entering into transactions for Oceana’s real estate, significant advance planning is recommended, including the development of a Master Plan. Doing so will permit the Navy to maximize its return from Oceana’s real estate and to insure the best neighbors for Oceana. In effect, the Navy is creating a new, large-scale master-planned real estate project. This project will be the single most significant real estate project for the Hampton Roads Region and the City of Virginia Beach in years. Advanced planning is typical in both the private and public sectors for large land areas proposed to be re-purposed. Such planning will take months, the dedication of capable professionals and public outreach. As part of the Master EUL, the tenant would coordinate with the many public, non-profit and private organizations to develop a master plan, which would be the result of a joint land use study of the tenant and the Navy. There may be funding available for planning from the Dept. of Defense’s Office of Economic Adjustment (OEA), the State, or other organizations and foundations. A master EUL could facilitate subleases on readily developable sites to “prime the pump” and give other potential sublease tenants confidence in the Future Base Design.

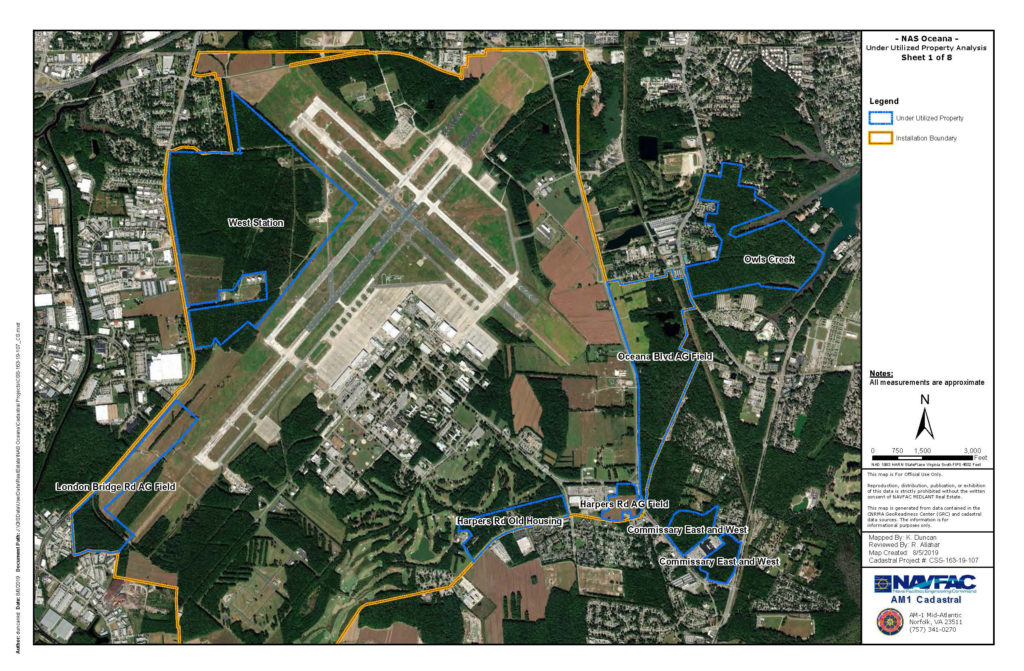

Figure 2: Master Planning is recommended to enable the Navy to maximize its return on NAS Oceana’s real estate

We propose that the Navy issue an RFP for a PPP partner to enter into a Master EUL which may including the following terms:

- Land

- All 7 sites included in the recent RFQs

- Golf Course/Shooting Range/Bowling Alley/Movie Theater/Water Park

- Any land included in a site specific EUL would be excluded.

- Term: 5 years (with right for tenant to propose extension to a new 50-year term with a single 25-year renewal at any time after Navy approval of an Oceana Real Estate Master Plan)

- Rent: In-Kind Services

- Planning Services

- Master Planning Oceana real estate assets

- Market analysis- demand for sites

- Entitlement of sites – Federal, State and Local

- Designation of specific development sites (particularly taking into consideration environmental impacts and related costs

- Shared Services

- Mowing/Landscaping

- Maintenance

- Road

- Utilities

- Water

- Sewer

- Drainage

- Fence

- Sign

- Buildings

- Installation of a new interior perimeter fence (type and location selected by the Navy)

- MWR

- Outsource operation of Core MWR facilities on-site

- Use of non-military off-site recreation facilities. Examples- golf course, bowling alley, movie theater, shooting range, fitness facility, etc.

- Swap of land (comparable leasehold terms or fee) outside, but near Oceana

- In-Kind services may be provided directly by the Tenant or by paying contractors to provide the services.

- Planning Services

- Funding from Sub-leases: The subleases can provide for payments by the subtenants into an escrow held by the Tenant/Sub Landlord for the purpose of funding In-Kind Services.

- Lenders: Lenders to the Tenant or the sub-tenants may take an assignment of the leasehold interest but will not have a lien on the Navy’s fee simple title. This means that the EUL is an “Unsubordinated Ground Lease.”

- Retained Rights: The Navy will retain the right to cancel the EUL or sub-leases if necessary, in the interests of National Security, but with appropriate compensation to the tenant(s) in possession.

Possible Site-Specific EULs

The Navy sought suggestions for possible action to achieve prompt benefits relating to Oceana’s real estate assets. The proposed PPP for a Master EUL referenced above contemplates a deliberative plan to maximize long-term value and is recommended since much of Oceana real estate is not “development-ready.” However, certain tracts could be either included within the Master EUL or separately addressed to test if market forces are ready to respond to a separate long-term EUL opportunity for each such tract. The tracts which could be considered are the following:

- MWR Land

- Golf Course (all or 9 holes)

- Officer’s Club

- Bowling Alley

- Fitness Centers

- Movie Theater

- Water Park

- Other Vacant Land

- All former Ag. Sites (fewer wetlands issues)

- Sites adjacent to Commissary

- Golf Course (all or 18 holes)

- Former Housing site (subject to wetlands mitigation area)

- Dominion Energy: As previously noted, we support a site-specific EUL with Dominion Energy for the 140-acre former horse stables area. The format for this EUL could be similar to the Dominion Energy Solar Farm lease, but with such changes as are appropriate. As a regulated utility and current EUL tenant, Dominion Energy’s lease may not require extensive modifications, so the transaction could proceed expeditiously. We believe this site is among the most marketable and developable sites in Oceana, so we recommend the Navy carefully consider the market value of the site before finalizing an EUL. Specifically, we recommend an independent, qualified appraiser provide an appraisal report and determine the current fair market value of the site.

Critical Elements for Success

- Balance the use of an EUL (preferably a master tenant lease) with other options (such as a City-Base option) to confirm an EUL is the proper choice.

- If an EUL is selected, negotiate a non-binding Letter of Intent with the tenant to define the critical terms.

- Consider using the Secretary of the Air Force for Installations, Environment, and Infrastructure’s (SAF/IEI) Lessons Learned document.4

- Hire an independent facilitator(s) familiar with EULs, Commercial Real Estate practices, City Government (if a master EUL), and Installation BOS Operations, tasked to guide both parties through the critical path.

City-Base/EFI Analysis

A City-Base (aka Efficient Facilities Initiative or EFI) is simply a transfer-leaseback for all or portions of a military installation. It trades the responsibility of ownership for the benefits of tenancy. The Efficient Facilities Initiative was implemented successfully between the City of San Antonio (aka, Brooks Development Authority) and the Air Force Material Command (aka, Brooks AFB). The FY00 Defense Appropriations Bill, 24 Oct 99, Section 8158 gave the Secretary of the Air Force authority to carry out a demonstration project at Brooks Air Force Base. Specifically, it was authorized in the July 13, 2000 defense installation budget (Public Law 106–246, 114 STAT. 520), titled the “Brooks Air Force Base Development Demonstration Project,” and described as the “Base Efficiency Project” in the authorization. This initiative carried with it all the goals and objectives found in the Navy’s Future Base Design Initiative for Oceana.

Roles, Relationships and Responsibilities

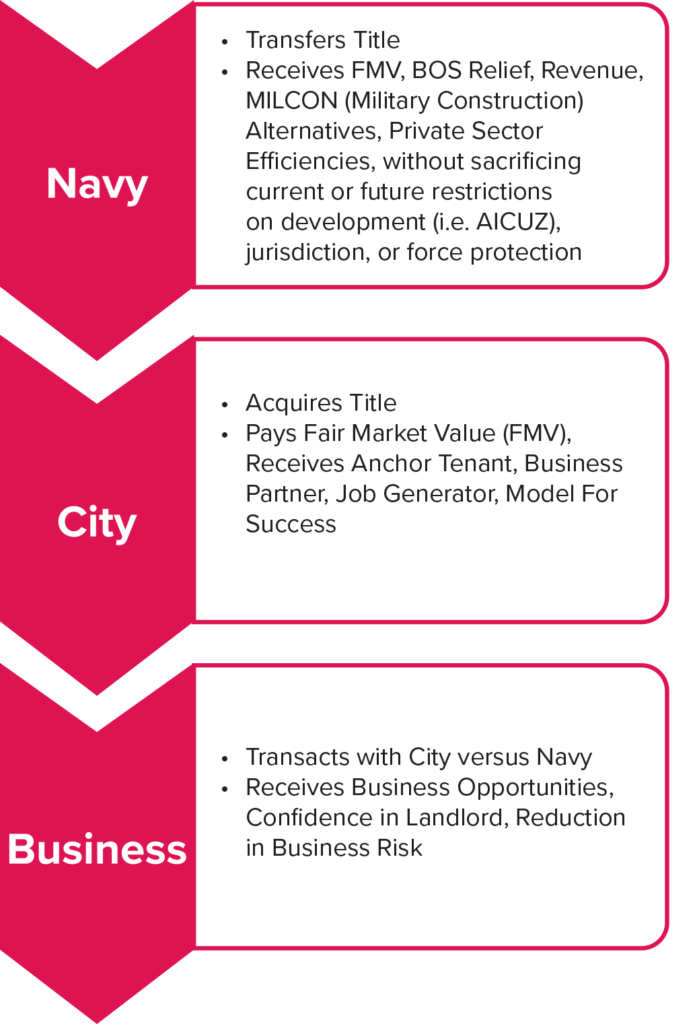

Any initiative that relies on external (public or private) participants needs to mutually benefit all parties. Working with public participants (government or non-profits) carries the added benefit that profit, in addition to cost, is not their overriding goal. Working directly with the private sector requires sensitivity to their return objectives, but they tend to operate with greater efficiency than the public sector. The key is to leverage the skills and objectives of all parties to achieve the Navy’s goals.

Figure 3: Leveraging Goals of All Parties

The Navy’s most pressing desire is a reduction in, or revenue against, Base Operating Support Costs. Through a transfer and leaseback, the Navy reduces costs in at least four (4) ways. First, the Navy would no longer be responsible for maintaining facilities through organic staff. It would have access to industry business practices through its landlord (City), requiring fewer employees. The City is not subject to the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) and can obtain goods and services much quicker from a broad array of sources than the Navy. The City can use its scale and buying power to generate greater efficiencies locally than the Navy. Finally, if the Navy elects to release any portion of its footprint for lease or sale by the City, it receives the value of its contribution in cash or in-kind.

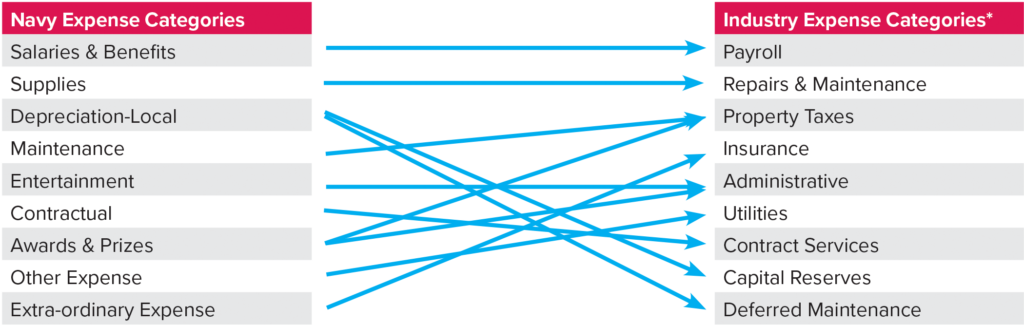

As the relationship develops, additional benefits will likely accrue as well. However, the first step in the process would be to develop a Cost Baseline Analysis. A Cost Baseline Analysis is a simple process of collecting all BOS costs at Oceana and arraying them in an industry format.

Figure 4: Cost Baseline Example

*We recommend indexing to the Institute of Real Estate Management (IREM) chart of accounts.

The Cost Baseline Analysis is a critical first step. It allows the Navy to compare its costs with industry costs to determine what its true costs are compared to industry. It also allows the Navy the ability to target and track results from Future Base Design efforts. In the previous example comparing an MWR activity to industry costs (reference Institute of Real Estate Management or Institute of Real Estate Management (IREM) chart of accounts) some costs are not allocated to MWR as they would be for an owner or tenant off-station. These BOS costs are accounted for and tracked, but just not allocated to tenant organizations. For example, Property Taxes in the private sector pay for police, fire, roads and utility infrastructure. All of those are costs borne by the installation, but not billed to the tenant organization, making the true costs to the Navy much higher for this particular activity.

In addition, the CRE® Consulting Corps recommends the Navy conduct a cost baseline analysis for the entire installation. While a City-Base/EFI transaction may not be practicable for the entire footprint, it is easier to reduce the footprint, and associated costs, than attempting to shave costs to isolate specific areas for cantonment.

A cost baseline analysis creates a starting point for the Navy to begin negotiating a City-Base/EFI transaction and/or an essential services agreement. Every installation’s cost profile is different, but as described previously, the total BOS Cost for Brooks AFB was roughly $52M. After completion of a Cost Baseline Analysis it was determined the true real estate costs were approximately $38M. The difference was attributed to business or enterprise activities versus the costs allocated to purely industry or real estate activities. Rather, there were $14M spent purely on businesses/enterprises (payroll, cost of goods sold, supplies, etc.) conducted inside Air Force buildings versus the real estate costs (maintenance & repair, payroll, utilities, etc.) associated with those buildings.

With $38M as their starting point the Air Force compared Brooks AFB costs to the real estate costs for similar facilities in the private sector and realized the industry costs were closer to $16M for the same activities in a commercial real estate development. When the City-Base/EFI transaction closed, a commercial property management company was hired by the Brooks Development Authority (BDA) and operating costs were reduced to $18M. The baseline BOS costs associated with facilities at Brooks AFB decreased by 50%.

A cost baseline analysis will be a critical first step for Oceana in any real estate privatization initiative.

There is no guarantee Oceana would see a 50% reduction in BOS costs, but without a cost baseline for comparison, there is no way to determine what its costs will be. Regardless, a cost baseline analysis will be a critical first step for Oceana in any real estate privatization initiative.

A City-Base structure affords the Navy new options for current and future facilities construction.

The City will benefit from this effort as well. Some City and community stakeholders may view a City-Base/EFI as a way to “BRAC-Proof” Oceana, but that should not be the City’s focus or goal. The City will find it benefits in ways that cannot be anticipated. The City would certainly be interested in reducing the operating cost to the Navy, its largest employer. It would be extending the size of the City’s developable area (subject to all Navy restrictions). The City would be able to generate tax revenue from private sector tenants that develop available land or locate in buildings on the installation. It would enhance its own economies of scale providing municipal services to the Navy and private sector occupants (a benefit to taxpayers). It would have the ability to market the installation to Navy-approved tenants to expand the local economy. Finally, if the missions at Oceana were moved as a result of a future BRAC, the City would have a significant head start on redevelopment. The table in Figure 5 details the essential differences between BRAC and a City-Base/EFI.

Figure 5: BRAC vs. City-Base/EFI

| BRAC | City-Base/EFI |

| Recommendations carry the force of law | Actions are voluntary |

| BRAC impacts only those installations included in approved recommendations | EFI can be applied to every installation to some degree |

| BRAC produces winners and losers | All communities and missions can be winners |

| Process is prescribed and driven by law | Process is flexible |

| Process may ignore workforce impacts | Workforce participation is desired |

| Savings derived mostly from manpower reductions | Savings derived from mission and function transition |

| Generates savings for the Dept. of Defense (DoD) | Generates savings for DoD and revenues for communities and the Installation |

Industry would also benefit as compatible businesses that may have located elsewhere could have a viable option to locate on Oceana, promoting economic expansion in the area. Furthermore, businesses or contractors who eschew FAR restrictions required to provide BOS services at NAS Oceana, can provide those services through the City without the time delays and red tape. Hence, industry can provide BOS support more freely and cost-effectively through the City, ultimately benefiting the Navy with more timely, lower cost, BOS support.

In summary, there are benefits to the Navy, City of Virginia Beach and Industry through a City-Base/EFI transaction. The financial benefits accrue more quickly than a protracted absorption period associated with EULs. The Navy is relieved of the burden of organically providing BOS services and/or learning to negotiate leases with the private sector. Rather, the Navy can focus on its mission rather than its duties as a landlord, and they can do so with a trusted partner, the City of Virginia Beach.

Common Questions and Concerns

Whenever the status quo is threatened there will always be questions, and rightfully so. The following address some of the frequently asked questions regarding a City-Base/EFI transaction.

Q: If a City-Base is so great why did they BRAC the Air Force Mission at Brooks City-Base?

A: The Air Force didn’t want to BRAC the missions at Brooks City-Base. Brooks City-Base became the lowest cost, best maintained installation to locate an Air Force mission. The Medical Joint Cross Service Group made the BRAC recommendation because they wanted to consolidate medical research operations into centers of excellence to conduct biomedical research. The MJCSG decision won out over the Air Forces wishes in the 2005 BRAC.

Q: Wait, are you suggesting we turn control of NAS Oceana to the City?

A: How much control the Navy wishes to transfer is completely up to them. Rather, the only thing that would transfer is the title to the property, in exchange for FMV. The Navy can lease back the entire footprint in perpetuity if it wishes. NAS Oceana can continue to manage the property they lease the way they would if they still held title to the land. However, that would generate no savings or revenue. How much or how little control the Navy desires will be paramount to any agreement with the City.

Q: How is security handled?

A: Through transaction negotiations with the City. The Navy can provide security for the entire installation or just the portions they wish, through its leasehold interest. There are many examples of military security on leased property (Crystal City Offices, Airport Hangers, Pier Support Facilities, Warehouses, etc.).

Q: What happens to our ability to restrict development on or around the Station?

A: Nothing, AICUZ (and all other) restrictions will remain in place and follow the chain of title by covenants, conditions and restrictions (CCRs).

Q: What if we need more space (structures) on the installation?

A: The Navy will have options. The Navy could use Military Construction (MILCON) to construct the structures they require in 10 -15 years at 3 to 4 times the cost of the private sector… or the Navy could ask their landlord to build a modern structure within 2 – 3 years at 25% to 33% of the cost of MILCON.

Q: Who would maintain the infrastructure (roads, utilities, etc.)?

A: The City would. The proportionate cost could be reimbursed by the Navy, and/or the City could replace aging infrastructure with bond financing through a Tax Increment Finance District (TIF).

Q: What is a TIF?

A: Tax increment financing (TIF) is a public financing method that is used as a subsidy for redevelopment, infrastructure, and other community-improvement projects in many countries, including the United States. Virginia cities, counties, and towns can help fund new development by creating special tax districts. A portion of the revenue from property taxes in those districts can be allocated to finance construction of sports stadiums, rail and bus systems, convention centers, and other “improvements.” If a TIF District encompasses Oceana, all taxes collected over a base level could be pledged to benefit Oceana and the Zone’s ability to finance more projects would grow with each project’s addition to the tax base.

Q: What authorities exist that allow the Navy to execute a transaction of this type?

A: While the modification to the BRAC process in 1997 (32 CFR 175.7(k)) allows for transfer and leaseback, the best option open to the Navy and the City is through special legislation. Fortunately, there is a precedent of a successful model and road map in Brooks City-Base making it more likely future congressional authority will be granted again. However, it will require broad support from a coalition of stakeholders including Navy, Community, State and Federal Leadership to achieve that objective.

There will be more questions if the Navy elects to proceed with a City-Base transaction, and many of them will no doubt be unique to Oceana. Regardless, the critical questions have all been asked and answered before. The important thing to remember is that the process is designed to address concerns and contingencies through collaboration. The transaction isn’t so rigid that the documents cannot anticipate future changes through covenants, codes and restrictions or CCRs that would also transfer with title to the property. The most important consideration is to make sure the right participants are part of the process.

City-Base Transaction Critical Path

The table in Figure 6 outlines the critical path for a City-Base transaction.

Figure 6: City-Base Critical Path Processes and Activities

| Estimated Timing* | 3 Months | 3 Months | 6 Months | 3 Months | Ongoing |

| Processes |

|

|

|

|

|

| Community Planning |

|

|

|

|

|

| Property Disposal |

|

|

|

|

|

| Environmental Impact Analysis |

|

|

|

||

| Environmental Transition |

|

|

|

|

|

| Installation/Infrastructure Management Transition |

|

|

|

|

|

| Personnel Transition |

|

|

|

|

*Estimated timing is subject to variables, see “SAF/IEI Lessons Learned and Recommendations for Process Improvement at Future Air Force Transfer and Leaseback Locations” report.5

Critical Elements for Success

While having a process road map is important to track and sustain progress there are four critical elements for the success of a City-Base transaction.

- Develop a clear options matrix with Navy leadership to determine the best course of action for the Navy to achieve Future Base Design objectives at NAS Oceana with the greatest probability for success.

- If a City-Base Option is selected, establish a non-binding Letter of Intent with the City to define and establish the Option as a joint objective for the Navy and the City at NAS Oceana.

- Study, question, and take appropriate actions in accordance with the SAF/IEI Lessons Learned document. 6

- Finally, jointly hire an independent facilitator(s) familiar with the City-Base/EFI transaction, Commercial Real Estate practices, City Government, and Installation BOS Operations, tasked to guide both parties through the critical path.

Including the key participants sets the stage for action.

These elements will clearly establish a path to codify the objectives of both parties, complete the transaction, and develop a smooth transition to achieve the desired results for the Navy’s Future Base Design Initiative. •

The Consulting Corps is The Counselors’ public service initiative. Members of The Counselors volunteer their time and expertise to help nonprofit and government entities by providing objective analysis, adaptive reuse strategies, and realistic action plans to leverage and maximize performance of real estate assets. For more information or to suggest a project that could benefit from Consulting Corps assistance, contact Samantha DeKoven. To learn more, visit cre.org/initiatives/consulting-corps.

Endnotes

1. “DOD Installation Services: Use of Intergovernmental Support Agreements Has Had Benefits, but Additional Information Would Inform Expansion.” U.S. Government Accountability Office, October 23, 2018. https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-19-4. ↩

2. “Air Force Enhanced Use Lease (EUL) Playbook.” Air Force Civil Engineer Center, August 29, 2016. https://www.afcec.af.mil/Portals/17/documents/EUL/AF%20EUL%20Playbook%20-%2020160829.pdf?ver=2016-10-06-110839-517. ↩

3. Ibid. ↩

4. The SAF/IEI’s Lessons Learned document is a classified internal Air Force document that reviewed lessons learned during the execution of the Air Force’s Efficient Facilities Initiative (EFI) that led to Brooks City-Base in San Antonio, Texas. (Formerly known as Installations, Environment, and Infrastructure, this department is now Energy, Installations, and Environment). ↩

5. Ibid. ↩

6. Ibid. ↩

Jerry Turner, CRE, shakes hands with Capt. John Hewitt in August 2021.

Jerry Turner, CRE, shakes hands with Capt. John Hewitt in August 2021.